Aktuell

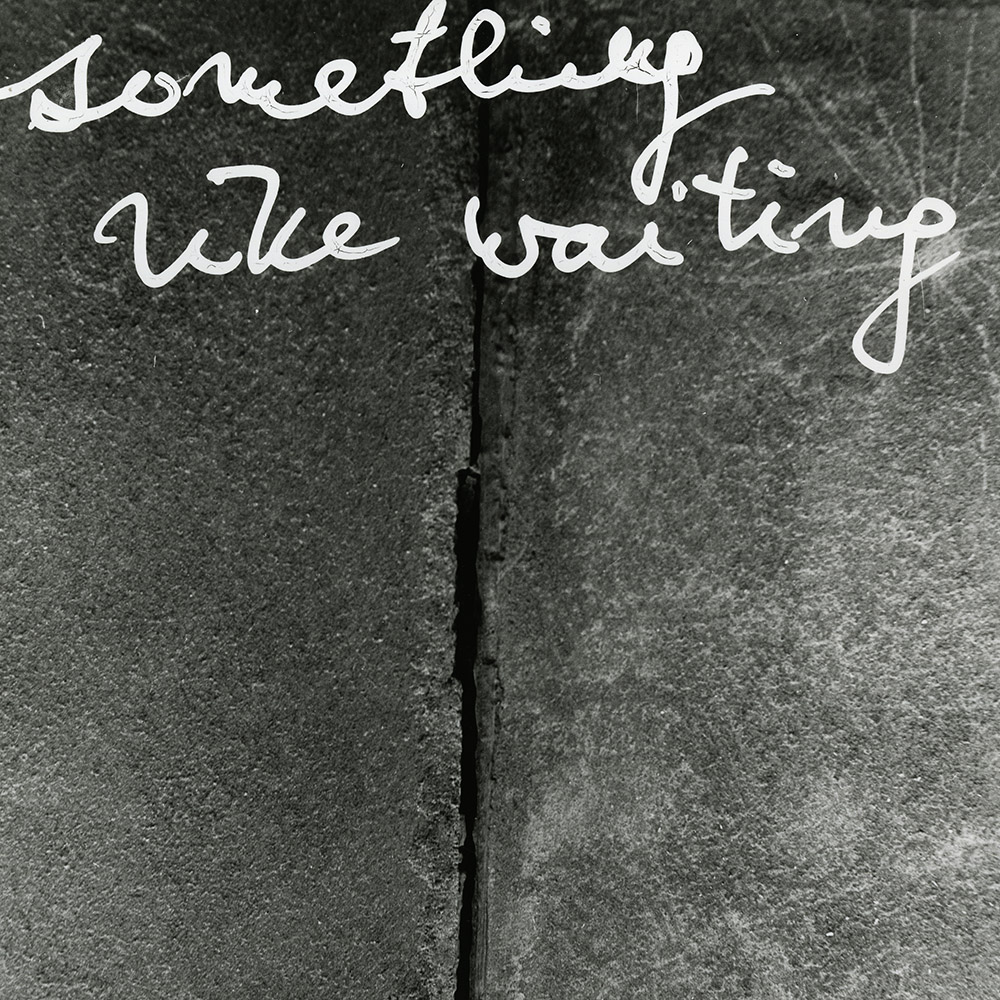

Jiří Valoch, Observing the Landscape II, Something like waiting, SW-Fotografie, 24,4 x 24,4 cm, 1974 © Jiří Valoch

PRE-PICTORIAL

JIŘÍ VALOCH

Eröffnung: 12.12.2025, 18.30 Uhr

Ausstellungsdauer: 13.–20.12.2025, 7.1.–14.3.2026

Öffnungszeiten: Mi–Sa, 10.30–17.00 Uhr

Jiří Valoch (*1946, Brno) ist ein tschechischer Konzeptkünstler, Kurator und Theoretiker, der seit den 1960er-Jahren eine zentrale Figur der mitteleuropäischen Avantgarde bildet. Sein Schaffen umfasst jenseits von Werken visueller und konkreter Poesie konzeptuelle Textarbeiten, Künstlerbücher und Textinstallationen, zudem minimalistische Happenings und Interventionen in der Natur.

Die Ausstellung PRE-PICTORIAL zeigt eine Auswahl früher Typogramme, Fotografien sowie eine Textinstallation, die für die Zeit der 1960er- und 1970er-Jahren nicht nur radikal reduziert erschienen, sondern auch in ganz eigener Art und Weise eine post- und non-semantische und visuell-poetische Sprache bedienten, die zeitgleich sich ausbildende internationale Formen der Konzeptkunst, visueller Poesie und teilweise auch der Land-Art nicht nur widerspiegelte, sondern wesentlich mitprägte.

Jiří Valoch studierte deutsche und tschechische Literatur und Ästhetik an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Masaryk-Universität in Brno (1965–1970). Seit 1966 war er auch als Kunstkritiker und Kurator tätig. Anfang der 1970er Jahre war er an der Organisation inoffizieller Ausstellungen in der gesamten Tschechoslowakei beteiligt. Von 1972 bis 2001 arbeitete er als Kurator im Haus der Kunst in Brno.

Die Ausstellung PRE-PICTORIAL zeigt eine Auswahl früher Typogramme, Fotografien sowie eine Textinstallation, die für die Zeit der 1960er- und 1970er-Jahren nicht nur radikal reduziert erschienen, sondern auch in ganz eigener Art und Weise eine post- und non-semantische und visuell-poetische Sprache bedienten, die zeitgleich sich ausbildende internationale Formen der Konzeptkunst, visueller Poesie und teilweise auch der Land-Art nicht nur widerspiegelte, sondern wesentlich mitprägte.

Jiří Valoch studierte deutsche und tschechische Literatur und Ästhetik an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Masaryk-Universität in Brno (1965–1970). Seit 1966 war er auch als Kunstkritiker und Kurator tätig. Anfang der 1970er Jahre war er an der Organisation inoffizieller Ausstellungen in der gesamten Tschechoslowakei beteiligt. Von 1972 bis 2001 arbeitete er als Kurator im Haus der Kunst in Brno.